Emergency Medicine: All Areas

Category: Abstract Submission

Emergency Medicine X

385 - Impact of Using a Pre-Completed Consent Form for Procedural Sedation in the Pediatric Emergency Department

Sunday, April 24, 2022

3:30 PM - 6:00 PM US MT

Poster Number: 385

Publication Number: 385.314

Publication Number: 385.314

Nichole McCollum, Children's National Hospital - D.C., DC, Washington, DC, United States; Olivia Silva, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC, United States; Laura Sigman, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC, United States; Kristen A. Breslin, Children's National Hospital, Washington, DC, United States; Jaclyn Kline, Children's National Health System, Washington, DC, United States

- OS

Olivia Silva, BA & Sc

Medical Student

George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences

Washington, District of Columbia, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Informed consent practices vary among providers and the information provided to caregivers is not standardized. Little is known about the impacts of using pre-completed consent in the pediatric emergency department (PED).

Objective: To compare 1)provider’s reported discussion and parental recall of benefits and risks of sedation and 2)the time providers report to complete the consent process, pre- and post-implementation of a pre-completed consent form. We hypothesize that parent’s recall of provider’s reported discussion will improve and the time for providers to complete the consent form will decrease in the post-implementation group.

Design/Methods: We surveyed a convenience sample of providers and parents after consent for procedural sedation in the PED of an academic children’s hospital before and after implementation of a pre-completed consent form. Recall of benefits and risks discussed reported on a Likert based scale by linked parent-provider dyads were compared. Chi-squared tests were used to compare the proportion of parents recalling a minimum number of elements across educational levels and the approximate time interval to complete the consent form.

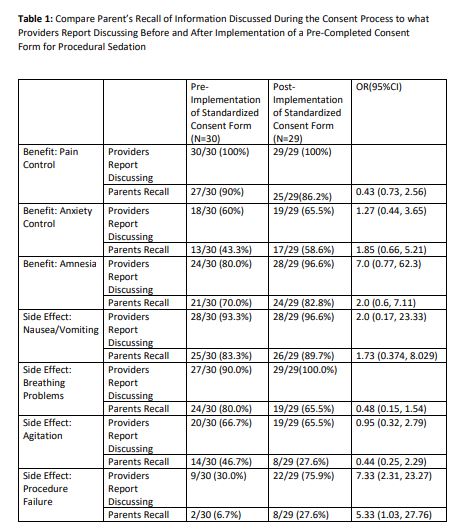

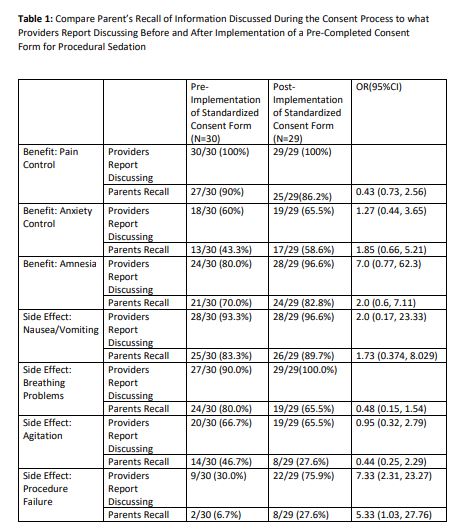

Results: Pre-intervention survey responses were received from 83 providers and 35 parents, including 30 paired responses. Post-intervention survey responses were received from 71 providers and 48 parents, including 29 paired responses. Providers were more likely to report discussion of the risk of failure to complete the procedure (OR 7.3; 95% CI 2.3-23.3) and parents were more likely to recall discussion of this risk (OR 5.3; 95% CI 1.0-27.8) in the post-intervention group (Table 1). Using the pre-completed consent form was associated with providers including discussion of at least two of the three benefits (84.0% v. 97.2%, p < 0.01) (Table 2). Using the pre-completed consent form was associated with providers including discussion of five out of the five risks (31% v. 67.7%, p < 0.01) and parents recalling these risks (5.7% v. 22.9%, p=0.03) (Table 2). There was no measurable difference in parent’s recall ability based on educational status. Time to complete the consent form as reported by providers decreased in the post-implementation group (OR 5.66; 95% CI 2.52-12.72) (Table 3).Conclusion(s): Overall, implementing a pre-completed consent form for procedural sedation in the PED was associated with better alignment of key consent elements between what providers report discussing and parents recalled during the consent process. Time for providers to complete the consent form decreased after implementation of the standardized consent form.

Table 1: Compare Parent’s Recall of Information Discussed During the Consent Process to what Providers Report Discussing Before and After Implementation of a Pre-Completed Consent Form for Procedural Sedation

Table 2: Comparison of Items Discussed Reported by Providers and Recalled by Parents Before and After Implementation of a Pre-completed Consent Form for Procedural Sedation.jpg) *Benefits: pain control, anxiety control, amnesia; ^Risks: nausea/vomiting, breathing problems, agitation, failure to complete procedure, medication allergy

*Benefits: pain control, anxiety control, amnesia; ^Risks: nausea/vomiting, breathing problems, agitation, failure to complete procedure, medication allergy

Objective: To compare 1)provider’s reported discussion and parental recall of benefits and risks of sedation and 2)the time providers report to complete the consent process, pre- and post-implementation of a pre-completed consent form. We hypothesize that parent’s recall of provider’s reported discussion will improve and the time for providers to complete the consent form will decrease in the post-implementation group.

Design/Methods: We surveyed a convenience sample of providers and parents after consent for procedural sedation in the PED of an academic children’s hospital before and after implementation of a pre-completed consent form. Recall of benefits and risks discussed reported on a Likert based scale by linked parent-provider dyads were compared. Chi-squared tests were used to compare the proportion of parents recalling a minimum number of elements across educational levels and the approximate time interval to complete the consent form.

Results: Pre-intervention survey responses were received from 83 providers and 35 parents, including 30 paired responses. Post-intervention survey responses were received from 71 providers and 48 parents, including 29 paired responses. Providers were more likely to report discussion of the risk of failure to complete the procedure (OR 7.3; 95% CI 2.3-23.3) and parents were more likely to recall discussion of this risk (OR 5.3; 95% CI 1.0-27.8) in the post-intervention group (Table 1). Using the pre-completed consent form was associated with providers including discussion of at least two of the three benefits (84.0% v. 97.2%, p < 0.01) (Table 2). Using the pre-completed consent form was associated with providers including discussion of five out of the five risks (31% v. 67.7%, p < 0.01) and parents recalling these risks (5.7% v. 22.9%, p=0.03) (Table 2). There was no measurable difference in parent’s recall ability based on educational status. Time to complete the consent form as reported by providers decreased in the post-implementation group (OR 5.66; 95% CI 2.52-12.72) (Table 3).Conclusion(s): Overall, implementing a pre-completed consent form for procedural sedation in the PED was associated with better alignment of key consent elements between what providers report discussing and parents recalled during the consent process. Time for providers to complete the consent form decreased after implementation of the standardized consent form.

Table 1: Compare Parent’s Recall of Information Discussed During the Consent Process to what Providers Report Discussing Before and After Implementation of a Pre-Completed Consent Form for Procedural Sedation

Table 2: Comparison of Items Discussed Reported by Providers and Recalled by Parents Before and After Implementation of a Pre-completed Consent Form for Procedural Sedation

.jpg) *Benefits: pain control, anxiety control, amnesia; ^Risks: nausea/vomiting, breathing problems, agitation, failure to complete procedure, medication allergy

*Benefits: pain control, anxiety control, amnesia; ^Risks: nausea/vomiting, breathing problems, agitation, failure to complete procedure, medication allergy