Public Health & Prevention

Category: Abstract Submission

Public Health & Prevention III

496 - Longitudinal Patterns of Childhood Adverse Experiences from Early Childhood to Adolescence: Implications for Intervention

Sunday, April 24, 2022

3:30 PM - 6:00 PM US MT

Poster Number: 496

Publication Number: 496.344

Publication Number: 496.344

Radhika S. Raghunathan, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States; Sara B. Johnson, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States; Kristin Voegtline, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States; Nicholas S. Ialongo, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Woodbine, MD, United States; Rashelle Musci, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Heallth, Baltimore, MD, United States

Radhika S. Raghunathan, MSPH, PhD

Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Baltimore, Maryland, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Adverse experiences in childhood can have detrimental impacts on life course health; variation in the timing, nature, severity, and chronicity of adversity is thought to explain variability in health and developmental outcomes among those exposed. However, few studies have empirically this level of complexity.

Objective: We sought to characterize multilevel patterns of adversity (individual, family, neighborhood) from childhood to adolescence.

Design/Methods: Participants

(n = 580) were children in a randomized universal preventive intervention trial in 1st grade followed until age 26. Parents reported on children’s lifetime

adversity through 1

st

grade. In grades 6-12, youth self-reported adverse life events in the past year and perceptions of their neighborhoods. Separate latent models were used to characterize patterns of adversity in early childhood, middle school, and high school. Changes in children’s adverse experiences over time and the timing of these changes were assessed using a mover-stayer model in a latent transition analysis framework.

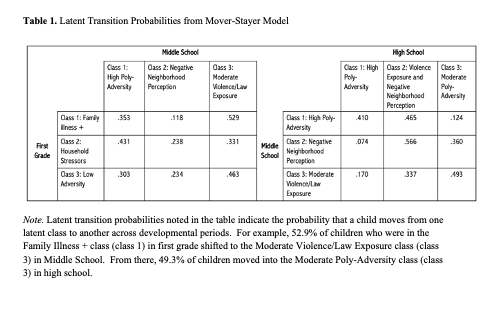

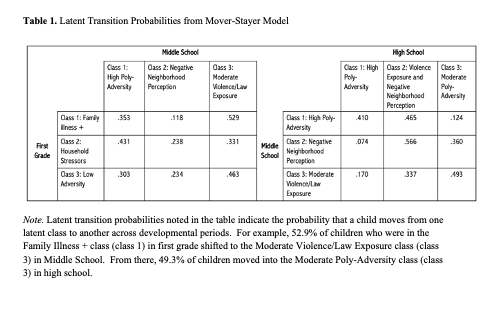

Results: On average, children were 6.2 years (SD = 0.36) at enrollment (46.2% girls and 85% Black). Results showed 3-class solutions in early childhood, middle school, and high school (Figure 1). Generally, a high poly-adversity class and a lower adversity class were observed at each time point, with differences in nature of adversity of the third class (i.e., early childhood family illness, middle school moderate violence/law exposure, high school negative neighborhood perception classes). The mover-stayer model indicated that almost all (96%) children had one or more changes in adversity class over time (Table 1); adverse exposures from childhood through adolescence changed substantially.Conclusion(s): We identified significant changes in children’s adverse exposures across key developmental periods. Treating adverse exposures as a static construct may limit the ability to detect salient variation in adversity and its impact over time. We suggest clinicians and researchers monitor exposures across multiple developmental points to capture complexities in children’s adverse experiences. Next, we will examine how changes in adversity classes are associated with young adult (ages 19-26) mental health, social, and behavioral outcomes to identify influential within-subject pathways for differential outcomes. This will be key for developing and implementing prevention and early interventions to mitigate negative effects of childhood adversities through the life course.

Figure 1. Composition of Latent Adversity Classes Over Time

Table 1. Latent Transition Probabilities from Mover-Stayer Model

Objective: We sought to characterize multilevel patterns of adversity (individual, family, neighborhood) from childhood to adolescence.

Design/Methods: Participants

(n = 580) were children in a randomized universal preventive intervention trial in 1st grade followed until age 26. Parents reported on children’s lifetime

adversity through 1

st

grade. In grades 6-12, youth self-reported adverse life events in the past year and perceptions of their neighborhoods. Separate latent models were used to characterize patterns of adversity in early childhood, middle school, and high school. Changes in children’s adverse experiences over time and the timing of these changes were assessed using a mover-stayer model in a latent transition analysis framework.

Results: On average, children were 6.2 years (SD = 0.36) at enrollment (46.2% girls and 85% Black). Results showed 3-class solutions in early childhood, middle school, and high school (Figure 1). Generally, a high poly-adversity class and a lower adversity class were observed at each time point, with differences in nature of adversity of the third class (i.e., early childhood family illness, middle school moderate violence/law exposure, high school negative neighborhood perception classes). The mover-stayer model indicated that almost all (96%) children had one or more changes in adversity class over time (Table 1); adverse exposures from childhood through adolescence changed substantially.Conclusion(s): We identified significant changes in children’s adverse exposures across key developmental periods. Treating adverse exposures as a static construct may limit the ability to detect salient variation in adversity and its impact over time. We suggest clinicians and researchers monitor exposures across multiple developmental points to capture complexities in children’s adverse experiences. Next, we will examine how changes in adversity classes are associated with young adult (ages 19-26) mental health, social, and behavioral outcomes to identify influential within-subject pathways for differential outcomes. This will be key for developing and implementing prevention and early interventions to mitigate negative effects of childhood adversities through the life course.

Figure 1. Composition of Latent Adversity Classes Over Time

Table 1. Latent Transition Probabilities from Mover-Stayer Model