Neonatal General

Category: Abstract Submission

Neonatology General 1: GI - Growth - Nutrition

266 - Intestinal Microbiome: The impact of open vs single room NICU design on bacterial colonization of the neonatal intestine

Friday, April 22, 2022

6:15 PM - 8:45 PM US MT

Poster Number: 266

Publication Number: 266.131

Publication Number: 266.131

Kelley Z. Kovatis, Christiana Care, Philadelphia, PA, United States; Amy Mackley, Christiana Care Health System, Newark, DE, United States; Shawn W. Polson, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States; Brewster Kingham, University of Delaware Sequencing & Genotyping Center, Newark, DE, United States; Deborah Tuttle, Christiana Care Health System, Newark, DE, United States; Stepen Eppes, ChristianaCare, Newark, DE, United States; David A. Paul, Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, Newark, DE, United States

- KK

Kelley Kovatis, MD (she/her/hers)

Attending Physician

ChristianaCare

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Critical microbiome development occurs before, during and after birth. Alterations in the normal development of the microbiome have been associated with childhood and adult disease. Multiple studies have observed altered microbiomes in premature infants. Although multifactorial, NICU environment may impact microbiome by altering care processes and acting as a bacterial reservoir. To date, no studies have assessed the impact NICU design has on the neonatal microbiome.

Objective: To determine how NICU design impacts the microbiome of premature infants over time by comparing stool samples obtained at week 1 and week 3 from infants admitted to a traditional open bay NICU (Open) to samples obtained from infants admitted to a private, single patient room NICU (Private).

Design/Methods: In this observational study of premature infants ( < 32 week gestation), stool and environmental samples (incubator, counter, floor) were obtained at week 1 and 4 of life. Samples were obtained from a single regional perinatal referral center. Open samples were obtained from 2018-2020 and Private samples from 2020-21. Microbial community profiling of 469 samples was performed on a ~2500bp amplicon of the rRNA operon (complete 16S-ITS-partial 23S). Amplicon sequence variants were identified using DADA2, taxonomic assignments were made using SBpipe with the Athena database (Shoreline Biome), and analysis and visualization of taxonomic, alpha, and beta diversity was performed in QIIME2.

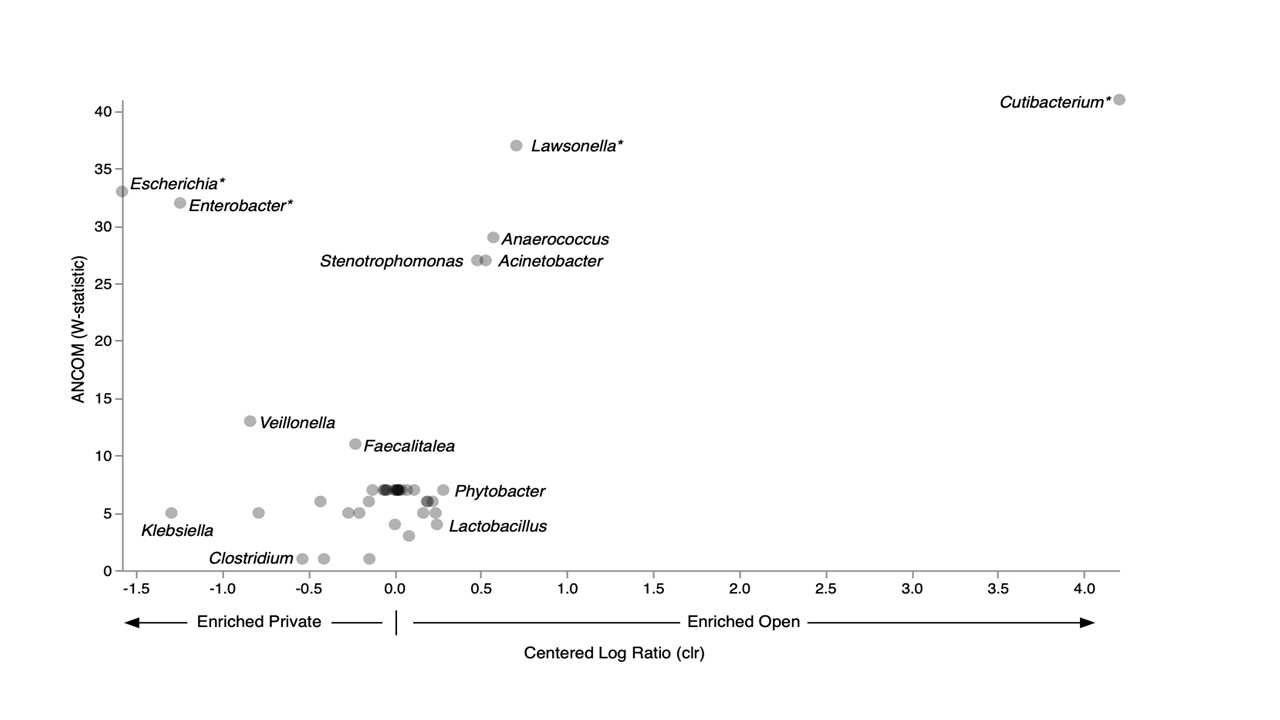

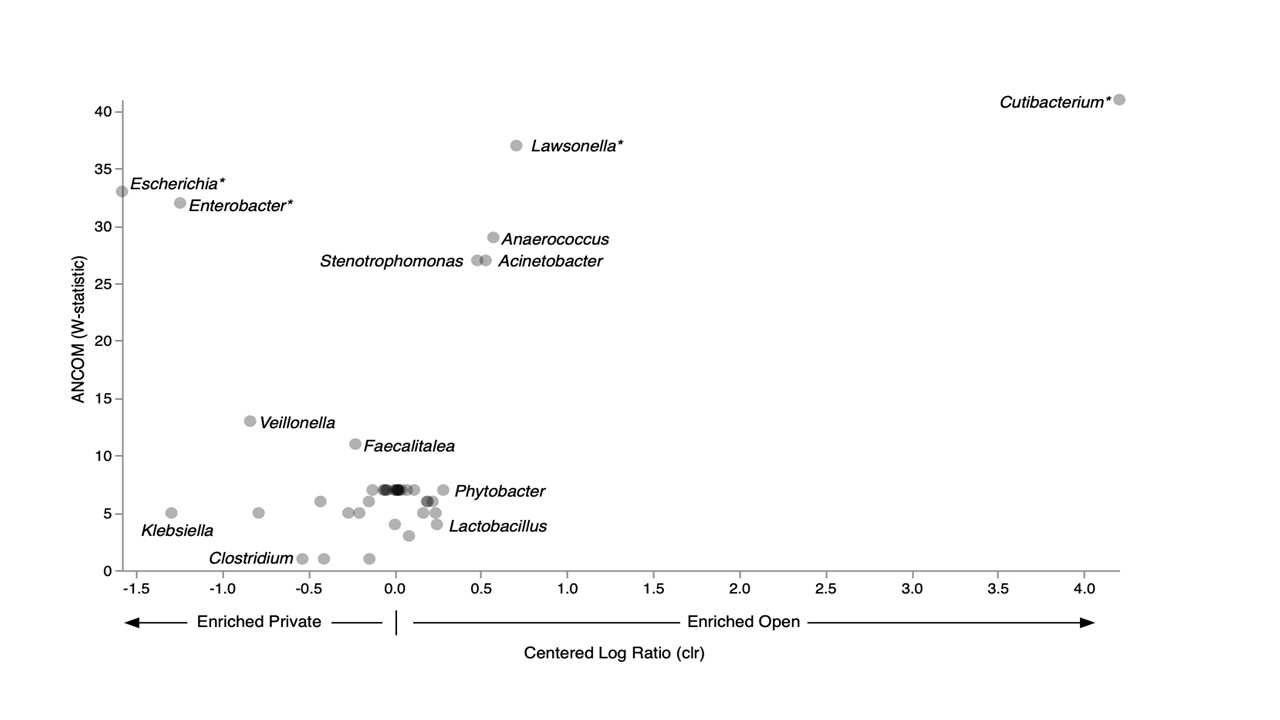

Results: 103 infants included in the study (49 Open v 57 Private). No difference in demographic or clinical data (Table 1) were noted. Stools obtained from Open were more phylogenetically diverse (Faith’s PD; Kruskall-Wallis p< 0.001) and had higher evenness (Pielou’s J’) compared to Private (K-W p=0.028). Cutibacterium and Lawsonella were enriched in Open and Enterobacteriaceae was enriched in Private (Fig 1). In Private, phylogenetic diversity (Faith’s PD) increased over time (Mann-Whitney U, p=0.019) and positively correlated with patient weight (Spearman, p=0.027). In private, observed enrichment of Staphylococcus epidermidis at week 1 with increased prevalence of Clostridia spp. by week 4.Conclusion(s): In our study sample, open bay rooms were associated with more phylogenetic diversity and higher evenness in the gut microbiome compared to open NICU rooms. NICU design may impact the neonatal microbiome. By elucidating the interaction between NICU design and microbiome, environmental strategies that minimize microbiome disruption may be implemented.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Data for Traditional, Open NICU and Private, Single Family NICU.jpg)

Figure 1. Taxonomic enrichment between open and private NICU as determined by analysis of composition (ANCOM). *significant enrichment (ANCOM; p < 0.05).

Objective: To determine how NICU design impacts the microbiome of premature infants over time by comparing stool samples obtained at week 1 and week 3 from infants admitted to a traditional open bay NICU (Open) to samples obtained from infants admitted to a private, single patient room NICU (Private).

Design/Methods: In this observational study of premature infants ( < 32 week gestation), stool and environmental samples (incubator, counter, floor) were obtained at week 1 and 4 of life. Samples were obtained from a single regional perinatal referral center. Open samples were obtained from 2018-2020 and Private samples from 2020-21. Microbial community profiling of 469 samples was performed on a ~2500bp amplicon of the rRNA operon (complete 16S-ITS-partial 23S). Amplicon sequence variants were identified using DADA2, taxonomic assignments were made using SBpipe with the Athena database (Shoreline Biome), and analysis and visualization of taxonomic, alpha, and beta diversity was performed in QIIME2.

Results: 103 infants included in the study (49 Open v 57 Private). No difference in demographic or clinical data (Table 1) were noted. Stools obtained from Open were more phylogenetically diverse (Faith’s PD; Kruskall-Wallis p< 0.001) and had higher evenness (Pielou’s J’) compared to Private (K-W p=0.028). Cutibacterium and Lawsonella were enriched in Open and Enterobacteriaceae was enriched in Private (Fig 1). In Private, phylogenetic diversity (Faith’s PD) increased over time (Mann-Whitney U, p=0.019) and positively correlated with patient weight (Spearman, p=0.027). In private, observed enrichment of Staphylococcus epidermidis at week 1 with increased prevalence of Clostridia spp. by week 4.Conclusion(s): In our study sample, open bay rooms were associated with more phylogenetic diversity and higher evenness in the gut microbiome compared to open NICU rooms. NICU design may impact the neonatal microbiome. By elucidating the interaction between NICU design and microbiome, environmental strategies that minimize microbiome disruption may be implemented.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Data for Traditional, Open NICU and Private, Single Family NICU

.jpg)

Figure 1. Taxonomic enrichment between open and private NICU as determined by analysis of composition (ANCOM). *significant enrichment (ANCOM; p < 0.05).