Health Equity/Social Determinants of Health

Category: Abstract Submission

Health Equity/Social Determinants of Health II

86 - A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Residential Mobility and Child Outcomes

Saturday, April 23, 2022

3:30 PM - 6:00 PM US MT

Poster Number: 86

Publication Number: 86.211

Publication Number: 86.211

Allison Lin, Cohen Children's Medical Center, Port Washington, NY, United States; Duy Q. Pham, Cohen Children's Medical Center, New York, NY, United States; Hannah E. Rosenthal, Cohen Children's Medical Center, Hauppauge, NY, United States; Ruth Milanaik, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Great Neck, NY, United States

- DP

Duy Q. Pham, BA

Feinstein Visiting Scholar

Cohen Children's Medical Center

New York, New York, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Residential mobility, or the process of changing residences, can have a substantial impact on health outcomes, as housing is known to be a social determinant of health. Moving to new neighborhoods, switching schools, and changes in the environment can be distressing for children. The demands associated with moving (losing support networks, economic hardship, etc.) could affect family resilience, or a family’s ability to adapt to difficult circumstances. Retrospective studies on adults have also shown that mental health problems later in life can be linked to childhood moves. There has not been a recent study using a national dataset on the immediate link between moving and outcomes among children in the US.

Objective: To examine associations between children’s residential mobility and exposures to ACEs, changes in family relationships, and mental/behavioral health conditions.

Design/Methods: Secondary analysis was performed on 126,827 eligible children in a combined dataset from the 2016-2019 National Survey of Children’s Health. Responses were separated into children who had never moved and children who had moved 1 time, 2 times, 3 times, and 4+ times. Family resilience, ACEs, and current medical diagnoses were reported by parents and dichotomized. Odds ratios (OR), adjusted odds ratios (aOR), and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were derived from logistic regression models, controlling for potential sociodemographic confounders.

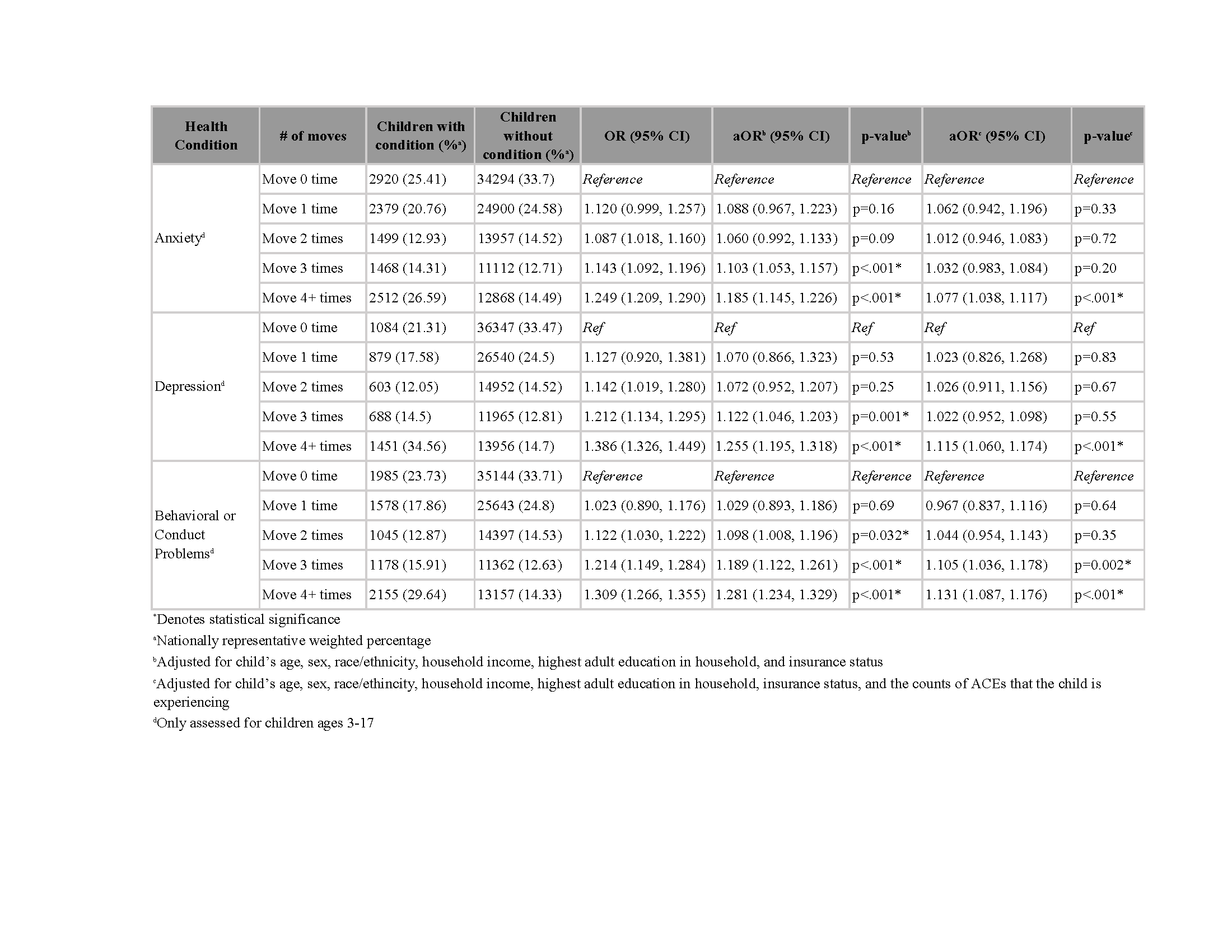

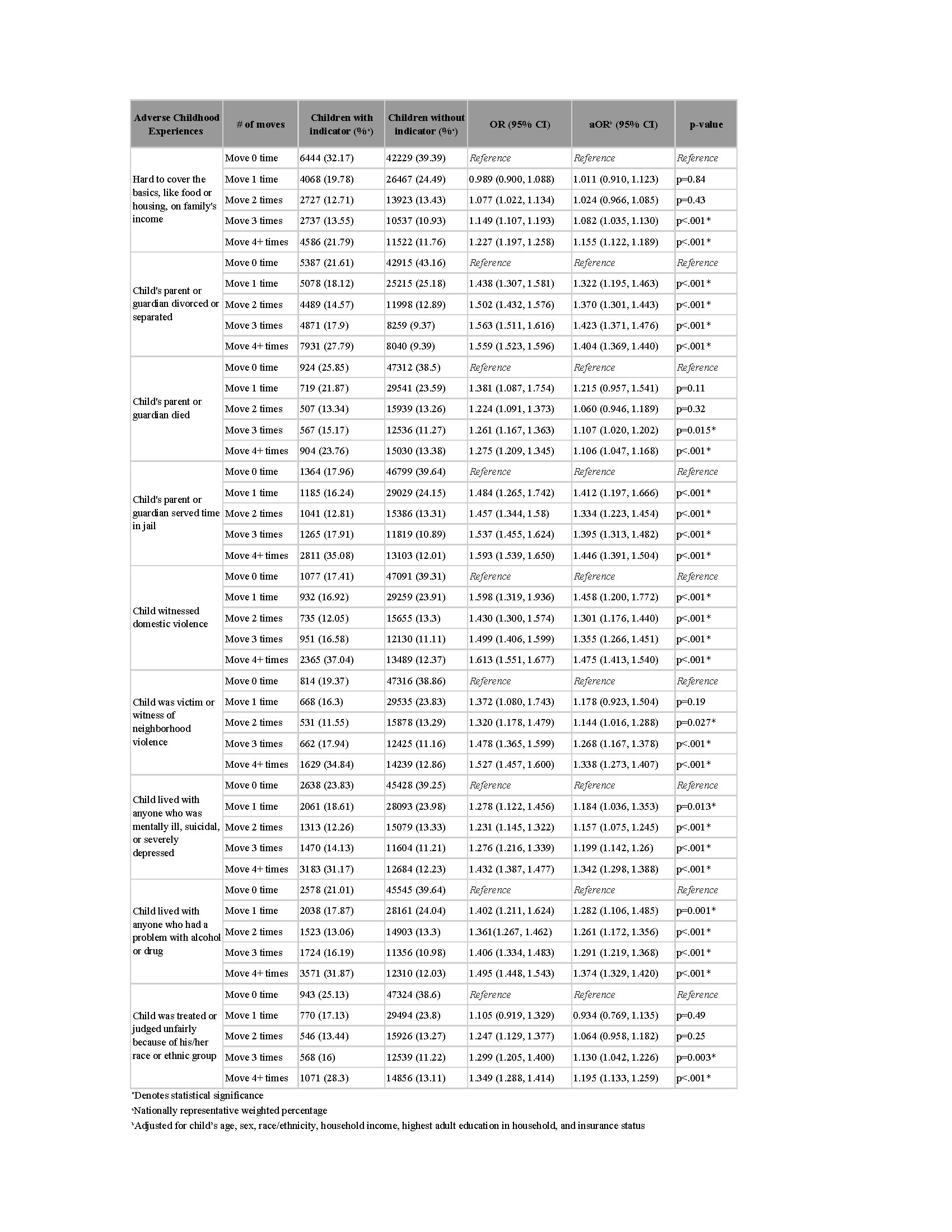

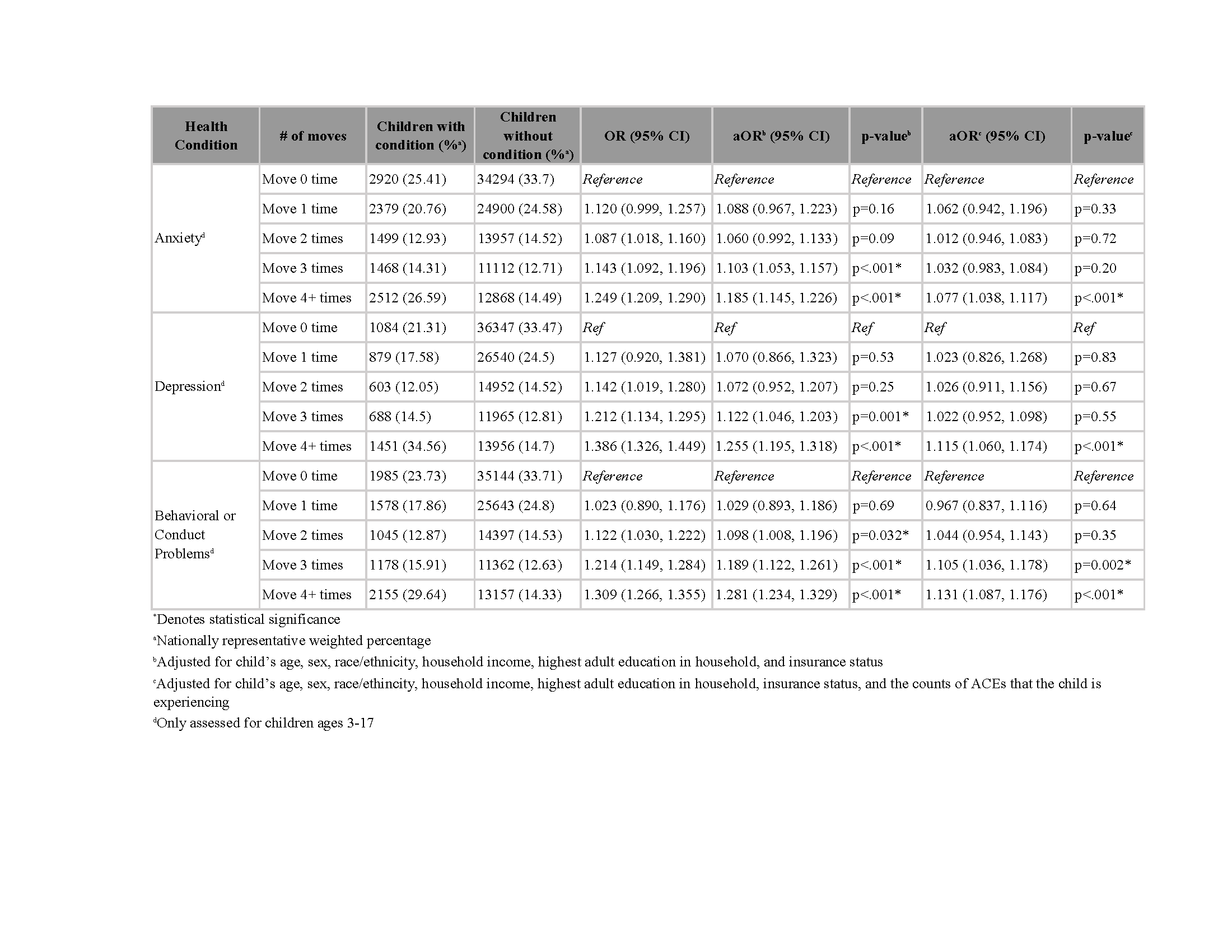

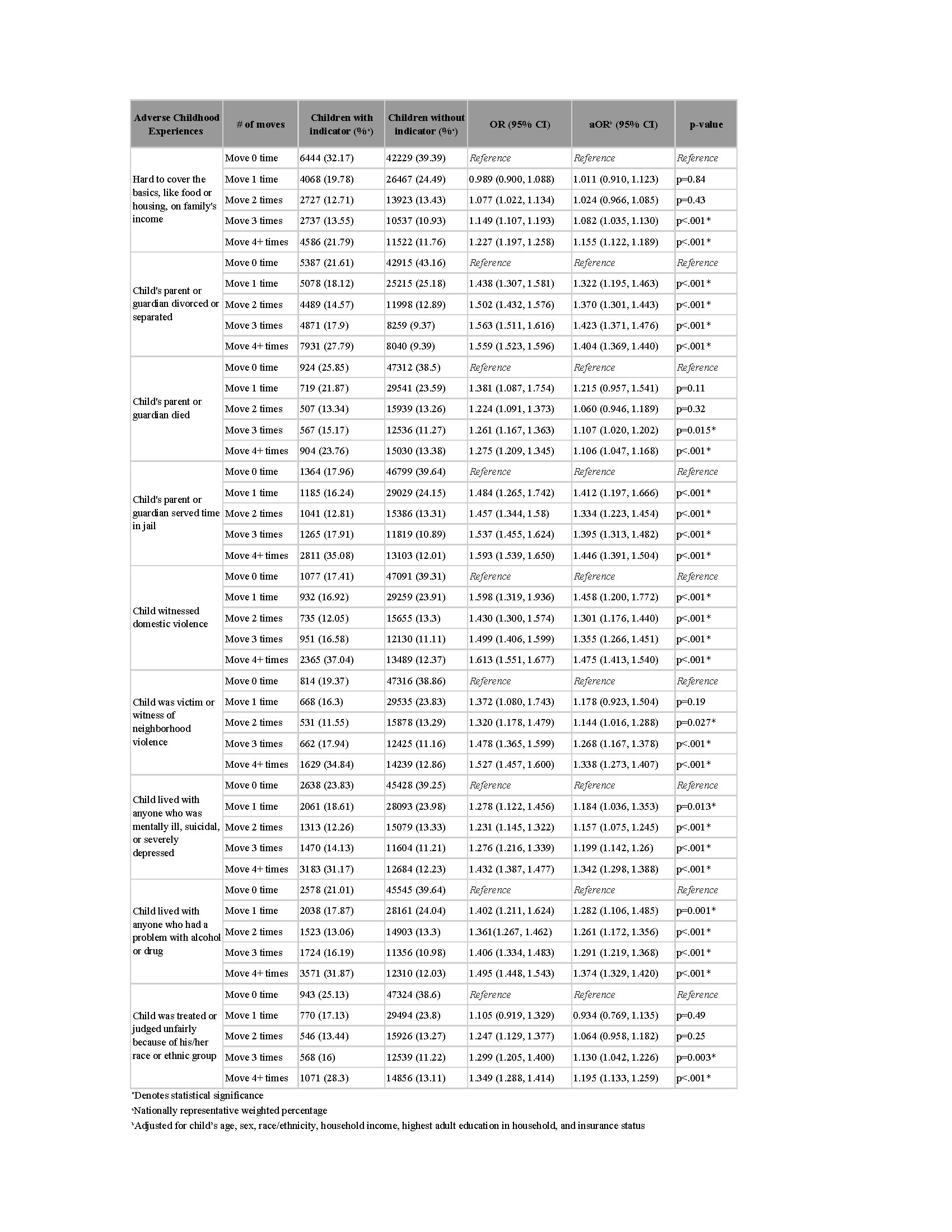

Results: Residential mobility was found to be a significant predictor of exposure to ACEs. Children who had moved 4+ times had a greater likelihood of living with a person with mental illness, suicidal ideation, or depression (aOR=1.342, 95% CI: [1.298, 1.388]). They were also more likely to live with someone who had alcohol/drug problems (aOR=1.374, 95% CI: [1.329, 1.420]) (Table 1). Increased residential mobility was associated with a higher chance of a diagnosis for anxiety, depression, and behavior/conduct problems even after controlling for the number of ACEs (Table 2). While there were few significant differences in family resilience indicators, parental aggravation was significantly higher for 3+ moves (Table 3).Conclusion(s): Children facing frequent residential mobility were more likely to be exposed to ACEs and to be diagnosed with mental health and behavioral conditions. Encouragingly, overall family resilience remained largely unchanged compared to children who had never moved. Pediatricians should be attentive to additional challenges in this population of children to ensure that they receive the medical and social support they need in order to flourish.

Table 1. Association between Residential Mobility Groups and Individual Adverse Childhood Experience Outcomes, 2016-2019 National Survey of Children’s Health

Table 2. Association between Residential Mobility Groups and Mental Health and Behavioral Conditions, 2016-2019 National Survey of Children’s Health

Objective: To examine associations between children’s residential mobility and exposures to ACEs, changes in family relationships, and mental/behavioral health conditions.

Design/Methods: Secondary analysis was performed on 126,827 eligible children in a combined dataset from the 2016-2019 National Survey of Children’s Health. Responses were separated into children who had never moved and children who had moved 1 time, 2 times, 3 times, and 4+ times. Family resilience, ACEs, and current medical diagnoses were reported by parents and dichotomized. Odds ratios (OR), adjusted odds ratios (aOR), and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were derived from logistic regression models, controlling for potential sociodemographic confounders.

Results: Residential mobility was found to be a significant predictor of exposure to ACEs. Children who had moved 4+ times had a greater likelihood of living with a person with mental illness, suicidal ideation, or depression (aOR=1.342, 95% CI: [1.298, 1.388]). They were also more likely to live with someone who had alcohol/drug problems (aOR=1.374, 95% CI: [1.329, 1.420]) (Table 1). Increased residential mobility was associated with a higher chance of a diagnosis for anxiety, depression, and behavior/conduct problems even after controlling for the number of ACEs (Table 2). While there were few significant differences in family resilience indicators, parental aggravation was significantly higher for 3+ moves (Table 3).Conclusion(s): Children facing frequent residential mobility were more likely to be exposed to ACEs and to be diagnosed with mental health and behavioral conditions. Encouragingly, overall family resilience remained largely unchanged compared to children who had never moved. Pediatricians should be attentive to additional challenges in this population of children to ensure that they receive the medical and social support they need in order to flourish.

Table 1. Association between Residential Mobility Groups and Individual Adverse Childhood Experience Outcomes, 2016-2019 National Survey of Children’s Health

Table 2. Association between Residential Mobility Groups and Mental Health and Behavioral Conditions, 2016-2019 National Survey of Children’s Health