Neonatal Quality Improvement

Category: Abstract Submission

Neonatal Quality Improvement I

203 - A Quality Improvement Initiative to Standardize Social Needs Screening and Referral in an Inner-City Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

Friday, April 22, 2022

6:15 PM - 8:45 PM US MT

Poster Number: 203

Publication Number: 203.126

Publication Number: 203.126

Erika G. Cordova Ramos, Boston Medical Center (BMC) - - Boston, MA, Jamacia Plain, MA, United States; Vanessa Torrice, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, United States; Maggie McGean, Boston University School of Medicine, Cambridge, MA, United States; Pablo Buitron de la Vega, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, United States; Judith Burke, boston medical center, boston, MA, United States; Donna M. Stickney, Boston Medical Center, Bridgewater, MA, United States; Margaret Parker, Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA, United States

Erika Cordova Ramos, MD (she/her/hers)

Assistant Professor of Pediatrics

Boston University School of Medicine

Wellesley, Massachusetts, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Screening and referral for social needs in clinical settings is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. While adoption of this practice has increased in outpatient pediatric settings, it has not yet come to scale in inpatient pediatric settings like the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Objective: In an inner-city level III NICU in Massachusetts, we aimed to (1) increase standardized social needs screening and referral to ≥60% of eligible families (length of stay ≥1 week); and (2) increase connection with community resources to ≥50% among families that report an unmet need and request assistance over a 12-month period.

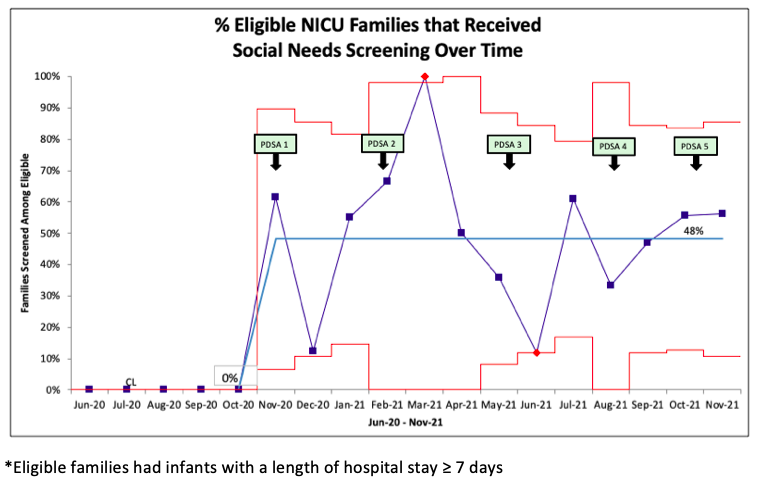

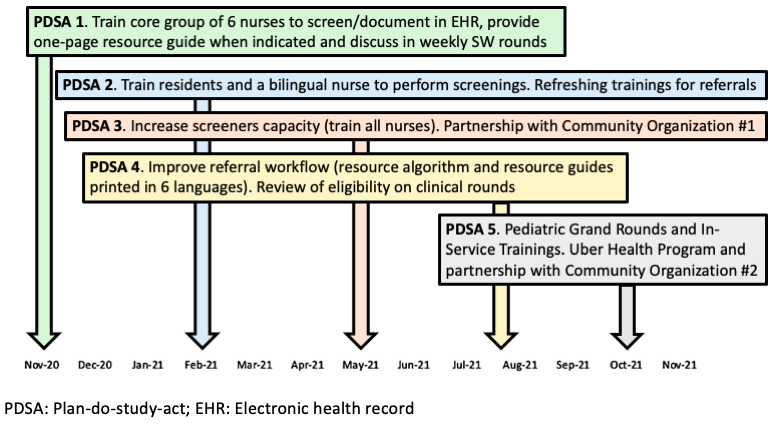

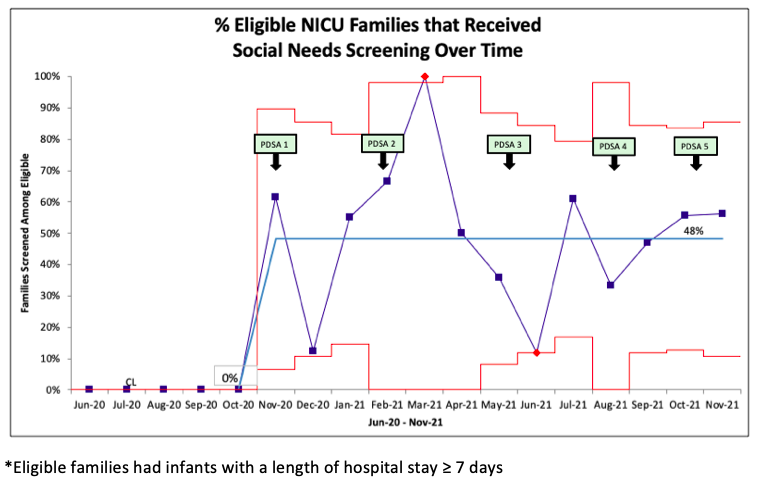

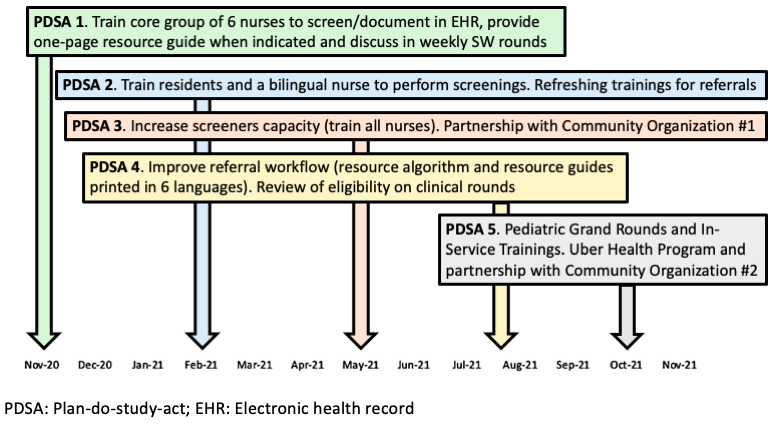

Design/Methods: After a needs assessment in the summer of 2020, our multidisciplinary team conducted a quality improvement project from Nov-2020 to Nov-2021. Plan-do-study-act cycles included adaptation of an evidence-informed social needs screening and referral intervention, staff education, integration into nursing clinical workflow and building community partnerships (Fig. 1). Main outcome measures were: (1) % eligible families screened among all eligible; and (2) % families that connected with community resources among those that reported a need and requested assistance. We examined outcome measures overall and by race/ethnicity and primary language. Our process measure was % referrals for unmet needs and our balancing measures were % declined screenings and qualitative feedback from staff and families. We used statistical process control to assess change over time and chi-square tests to compare our main outcomes among racial/ethnic and language groups.

Results: Rates of screening increased from 0 to 48% (Fig. 2). Among 91 families screened, 81% had ≥1 and 60% had ≥2 (range 2 to 5) unmet needs. Overall, 173 needs were reported and families desired assistance for 146 (84%). Education, employment, transportation and food were the most prevalent domains. Among families that reported an unmet need and requested assistance, 97% received referrals. Among those with referrals, the mean rate of connection with community resources was 31% and increased over time (Fig. 3). There were no significant differences in outcomes by race/ethnicity or language. Zero families declined screening and feedback from staff and families was overall positive although specific barriers were identified (i.e. workflow, capacity to follow through).Conclusion(s): Implementing standardized social needs screening and referral was feasible in a busy, inner-city NICU and revealed a substantial burden of unmet needs among NICU families.

Figure 1. Plan-Do-Study Act Timeline

Figure 2. SPC Chart for Unmet Social Needs Screening Over Time Among 189 Eligible* Families

Objective: In an inner-city level III NICU in Massachusetts, we aimed to (1) increase standardized social needs screening and referral to ≥60% of eligible families (length of stay ≥1 week); and (2) increase connection with community resources to ≥50% among families that report an unmet need and request assistance over a 12-month period.

Design/Methods: After a needs assessment in the summer of 2020, our multidisciplinary team conducted a quality improvement project from Nov-2020 to Nov-2021. Plan-do-study-act cycles included adaptation of an evidence-informed social needs screening and referral intervention, staff education, integration into nursing clinical workflow and building community partnerships (Fig. 1). Main outcome measures were: (1) % eligible families screened among all eligible; and (2) % families that connected with community resources among those that reported a need and requested assistance. We examined outcome measures overall and by race/ethnicity and primary language. Our process measure was % referrals for unmet needs and our balancing measures were % declined screenings and qualitative feedback from staff and families. We used statistical process control to assess change over time and chi-square tests to compare our main outcomes among racial/ethnic and language groups.

Results: Rates of screening increased from 0 to 48% (Fig. 2). Among 91 families screened, 81% had ≥1 and 60% had ≥2 (range 2 to 5) unmet needs. Overall, 173 needs were reported and families desired assistance for 146 (84%). Education, employment, transportation and food were the most prevalent domains. Among families that reported an unmet need and requested assistance, 97% received referrals. Among those with referrals, the mean rate of connection with community resources was 31% and increased over time (Fig. 3). There were no significant differences in outcomes by race/ethnicity or language. Zero families declined screening and feedback from staff and families was overall positive although specific barriers were identified (i.e. workflow, capacity to follow through).Conclusion(s): Implementing standardized social needs screening and referral was feasible in a busy, inner-city NICU and revealed a substantial burden of unmet needs among NICU families.

Figure 1. Plan-Do-Study Act Timeline

Figure 2. SPC Chart for Unmet Social Needs Screening Over Time Among 189 Eligible* Families