Health Equity/Social Determinants of Health

Category: Abstract Submission

Health Equity/Social Determinants of Health III

103 - Associations between Poverty, Neighborhood Cohesion and Child Mental Health: A representative cross-sectional study of children in Ontario, Canada

Saturday, April 23, 2022

3:30 PM - 6:00 PM US MT

Poster Number: 103

Publication Number: 103.212

Publication Number: 103.212

Anne E. Fuller, McMaster University, Waterloo, ON, Canada; James R. Dunn, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada; Katholiki Georgiades, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

Anne E. Fuller, MD, MS

PhD Student

McMaster University

Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

Presenting Author(s)

Background: While poverty is a well-established risk factor for poorer child health outcomes, an increasing body of evidence indicates that safe and supportive neighborhoods may be protective for child mental health. There is limited research examining the extent to which neighborhood factors offer protection in the context of poverty.

Objective: 1) To quantify associations between household poverty and child mental health; 2) To determine the extent to which the association between poverty and child mental health varies by neighborhood, and 3) To assess whether NC modifies the association between poverty and child mental health

Design/Methods: Data come from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study, a cross-sectional study of 10,802 children in 6,537 households across 484 neighborhoods in Ontario, Canada. Independent variables were household poverty and neighborhood cohesion (NC). Dependent variables were validated, parent reported scores on measures of: 1) externalizing disorders (oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder); 2) attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); 3) internalizing disorders (depression and generalized anxiety disorder). We used linear mixed-effects models to account for clustered sampling by households and neighborhoods with random intercepts at the household and neighborhood level. We used four sequential models to measure associations with mental health: 1) the fixed effects of poverty and 2) adding random slope of poverty at neighborhood level; 3) fixed effects of NC; and 4) testing for interaction between poverty and NC. Models were adjusted for sociodemographic covariates.

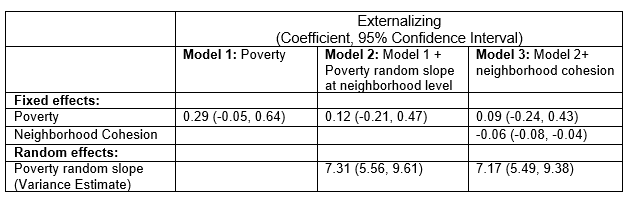

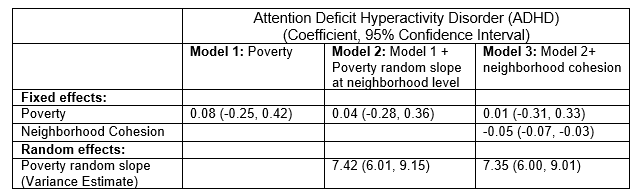

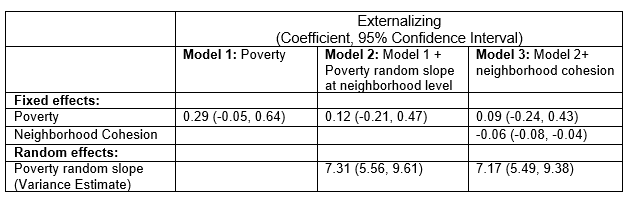

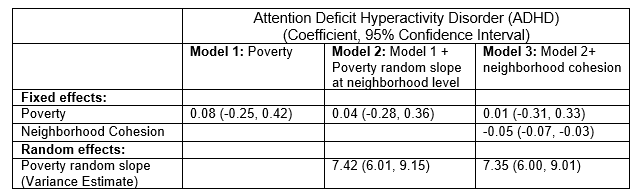

Results: 7,148 participants were included. About 16% of households reported income below the poverty level. Those with poverty reported lower NC. Poverty was not directly associated with mental health outcomes. The association between poverty and each outcome varied significantly by neighborhood. Higher NC was associated with lower scores for externalizing and ADHD regardless of income (Tables 1-3). For internalizing problems, NC was protective only for children without poverty (interaction term p= 0.085). Conclusion(s): In this representative sample of Ontario children, neighborhood cohesion was associated with better mental health outcomes, but children from low-income households may not receive equal benefits. Poverty may lead to greater needs which exceed these protective effects or poverty may exclude families from these benefits. Understanding the mechanisms of these relationships can help guide policies aimed at reducing income-related inequities in child mental health.

Associations between Poverty, Neighborhood Cohesion and Externalizing Models adjusted for child: age, sex, history of developmental condition; parent: age, race/ethnicity, education, immigration status; household urbanicity, family composition (lone parent or other)

Models adjusted for child: age, sex, history of developmental condition; parent: age, race/ethnicity, education, immigration status; household urbanicity, family composition (lone parent or other)

Table 2: Associations between Poverty, Neighborhood Cohesion and ADHD Models adjusted for child: age, sex, history of developmental condition; parent: age, race/ethnicity, education, immigration status; household urbanicity, family composition (lone parent or other)

Models adjusted for child: age, sex, history of developmental condition; parent: age, race/ethnicity, education, immigration status; household urbanicity, family composition (lone parent or other)

Objective: 1) To quantify associations between household poverty and child mental health; 2) To determine the extent to which the association between poverty and child mental health varies by neighborhood, and 3) To assess whether NC modifies the association between poverty and child mental health

Design/Methods: Data come from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study, a cross-sectional study of 10,802 children in 6,537 households across 484 neighborhoods in Ontario, Canada. Independent variables were household poverty and neighborhood cohesion (NC). Dependent variables were validated, parent reported scores on measures of: 1) externalizing disorders (oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder); 2) attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); 3) internalizing disorders (depression and generalized anxiety disorder). We used linear mixed-effects models to account for clustered sampling by households and neighborhoods with random intercepts at the household and neighborhood level. We used four sequential models to measure associations with mental health: 1) the fixed effects of poverty and 2) adding random slope of poverty at neighborhood level; 3) fixed effects of NC; and 4) testing for interaction between poverty and NC. Models were adjusted for sociodemographic covariates.

Results: 7,148 participants were included. About 16% of households reported income below the poverty level. Those with poverty reported lower NC. Poverty was not directly associated with mental health outcomes. The association between poverty and each outcome varied significantly by neighborhood. Higher NC was associated with lower scores for externalizing and ADHD regardless of income (Tables 1-3). For internalizing problems, NC was protective only for children without poverty (interaction term p= 0.085). Conclusion(s): In this representative sample of Ontario children, neighborhood cohesion was associated with better mental health outcomes, but children from low-income households may not receive equal benefits. Poverty may lead to greater needs which exceed these protective effects or poverty may exclude families from these benefits. Understanding the mechanisms of these relationships can help guide policies aimed at reducing income-related inequities in child mental health.

Associations between Poverty, Neighborhood Cohesion and Externalizing

Models adjusted for child: age, sex, history of developmental condition; parent: age, race/ethnicity, education, immigration status; household urbanicity, family composition (lone parent or other)

Models adjusted for child: age, sex, history of developmental condition; parent: age, race/ethnicity, education, immigration status; household urbanicity, family composition (lone parent or other)Table 2: Associations between Poverty, Neighborhood Cohesion and ADHD

Models adjusted for child: age, sex, history of developmental condition; parent: age, race/ethnicity, education, immigration status; household urbanicity, family composition (lone parent or other)

Models adjusted for child: age, sex, history of developmental condition; parent: age, race/ethnicity, education, immigration status; household urbanicity, family composition (lone parent or other)