Health Services Research

Category: Abstract Submission

Health Services Research I

192 - Health Insurance Coverage Disruptions Among Children with a History of Adversity

Sunday, April 24, 2022

3:30 PM - 6:00 PM US MT

Poster Number: 192

Publication Number: 192.319

Publication Number: 192.319

Chidiogo Anyigbo, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, United States; Emmalee Todd, Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, United States; Dmitry Tumin, Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, United States; Jennifer Kusma, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

.jpg)

Chidiogo Anyigbo, MD, MPH

Instructor

Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center

Children's National Hospital

Cincinnati, Ohio, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are forms of social and medical complexity that influence children’s healthcare needs. It is unclear whether children who endure ACEs are at a higher risk of either continuous or intermittent lack of health insurance which may limit access to needed care.

Objective: To examine the association between ACE score and having a health insurance coverage gap in a 12-month period. Secondarily, to examine whether ACE exposure was associated with specific reasons for health insurance coverage gaps.

Design/Methods: We included children ages 0-17 years from the cross-sectional 2016-2020 National Survey of Children’s Health. Exposure to ACEs was categorized as 0, 1, 2, 3, or ≥4. Insurance coverage was coded into 4 mutually exclusive groups: year-round private, year-round public, year-round un-insured, and coverage gap. Secondary outcomes included 6 specific reasons for coverage gaps.

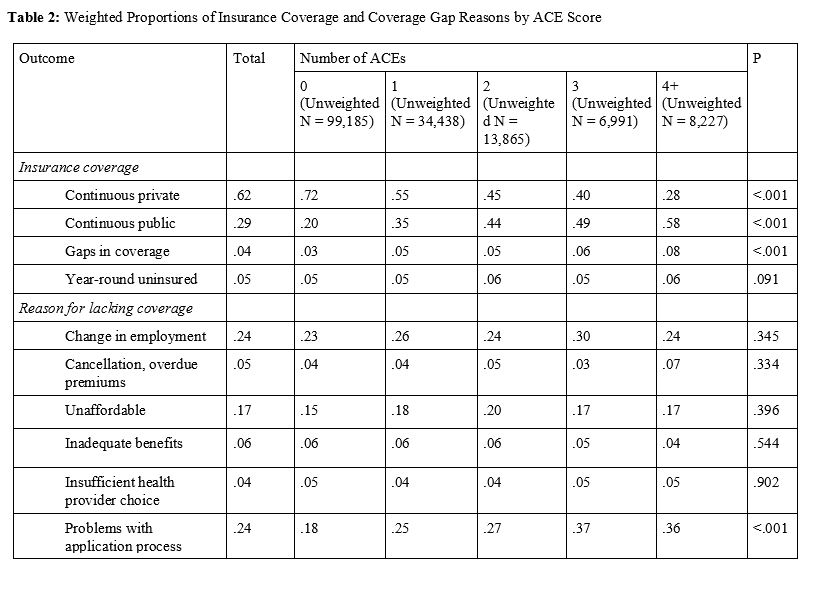

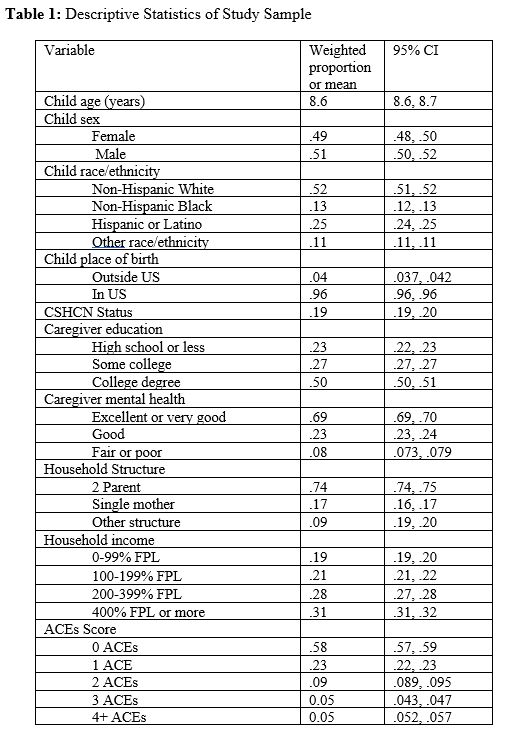

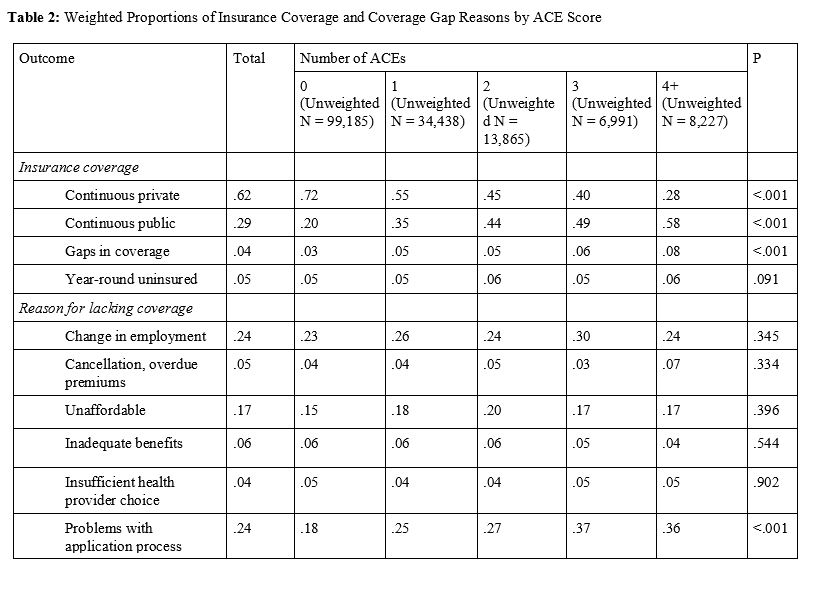

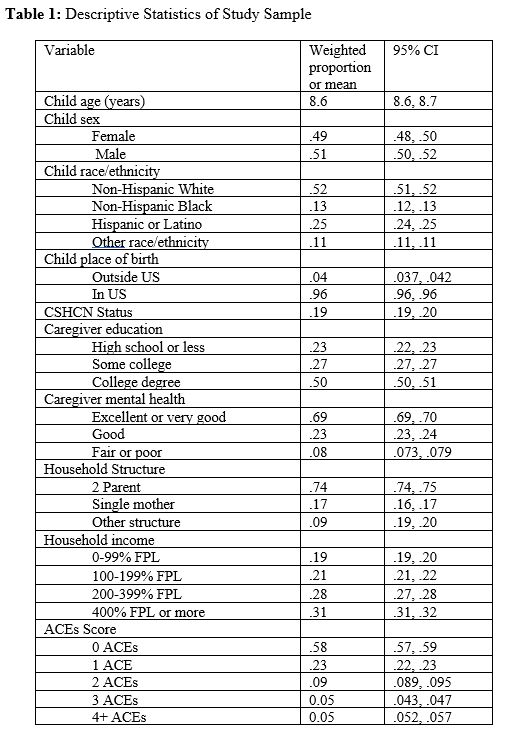

Results: Our analysis of 12-month insurance coverage included 162,706 children. Forty-two percent of children endured ≥1 ACEs (Table 1), and 4% had an insurance coverage gap (Table 2). On multivariable multinomial logistic regression analysis, children with 4+ ACEs had a higher likelihood of insurance coverage gaps rather than having year-round private insurance (relative risk ratio [RRR]:3.82; 95% CI:2.90-5.02), year-round public insurance (RRR:1.33; 95% CI:1.01-1.74), or year-round un-insurance (RRR:2.24; 95% CI:1.55-3.23) when compared to children with 0 ACEs (Table 3). Among 9,481 children with a period of un-insurance in the last 12 months, change in employer and problems with the application process were the most common reasons for the coverage gap (Table 2). Of the 6 reasons for lacking coverage, insurance coverage gap due to problems with the application process was the only reason associated with exposure to ACEs. Children who endured 4+ ACEs had 2.17 higher odds (95% CI:1.47-3.21) of a coverage gap due to the application or renewal process, compared to children with 0 ACEs (results not shown). Conclusion(s): Exposure to ACEs is uniquely associated with having health insurance coverage gaps above any association of ACEs with year-round private, public, or un-insurance. Additionally, increased exposure to ACEs is uniquely associated with experiencing coverage gaps due to administrative burden of enrollment or renewal. This finding is relevant as health insurance coverage expanded during the COVID pandemic will soon begin renewal processes. Policy changes to reduce administrative burdens may improve health insurance stability among children who endure ACEs.

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics of Study Sample

Table 2: Weighted Proportions of Insurance Coverage and Coverage Gap Reasons by ACE Score

Objective: To examine the association between ACE score and having a health insurance coverage gap in a 12-month period. Secondarily, to examine whether ACE exposure was associated with specific reasons for health insurance coverage gaps.

Design/Methods: We included children ages 0-17 years from the cross-sectional 2016-2020 National Survey of Children’s Health. Exposure to ACEs was categorized as 0, 1, 2, 3, or ≥4. Insurance coverage was coded into 4 mutually exclusive groups: year-round private, year-round public, year-round un-insured, and coverage gap. Secondary outcomes included 6 specific reasons for coverage gaps.

Results: Our analysis of 12-month insurance coverage included 162,706 children. Forty-two percent of children endured ≥1 ACEs (Table 1), and 4% had an insurance coverage gap (Table 2). On multivariable multinomial logistic regression analysis, children with 4+ ACEs had a higher likelihood of insurance coverage gaps rather than having year-round private insurance (relative risk ratio [RRR]:3.82; 95% CI:2.90-5.02), year-round public insurance (RRR:1.33; 95% CI:1.01-1.74), or year-round un-insurance (RRR:2.24; 95% CI:1.55-3.23) when compared to children with 0 ACEs (Table 3). Among 9,481 children with a period of un-insurance in the last 12 months, change in employer and problems with the application process were the most common reasons for the coverage gap (Table 2). Of the 6 reasons for lacking coverage, insurance coverage gap due to problems with the application process was the only reason associated with exposure to ACEs. Children who endured 4+ ACEs had 2.17 higher odds (95% CI:1.47-3.21) of a coverage gap due to the application or renewal process, compared to children with 0 ACEs (results not shown). Conclusion(s): Exposure to ACEs is uniquely associated with having health insurance coverage gaps above any association of ACEs with year-round private, public, or un-insurance. Additionally, increased exposure to ACEs is uniquely associated with experiencing coverage gaps due to administrative burden of enrollment or renewal. This finding is relevant as health insurance coverage expanded during the COVID pandemic will soon begin renewal processes. Policy changes to reduce administrative burdens may improve health insurance stability among children who endure ACEs.

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics of Study Sample

Table 2: Weighted Proportions of Insurance Coverage and Coverage Gap Reasons by ACE Score