Child Abuse & Neglect

Category: Abstract Submission

Child Abuse & Neglect I

211 - Acceptability and Feasibility of a Family Centered Care Model for Intimate Partner Violence

Monday, April 25, 2022

3:30 PM - 6:00 PM US MT

Poster Number: 211

Publication Number: 211.401

Publication Number: 211.401

Gunjan Tiyyagura, yale university school of medicine, New Haven, CT, United States; Paula Schaeffer, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States; Marcie gawel, Yale New Haven Hospital & Yale University, Meriden, CT, United States; Ashley S. Frechette, Connecticut Coalition Against Domestic Violence, Glastonbury, CT, United States; Kristen Hammel, Yale Center for Traumatic Stress and Recovery, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States; Destanee Crawley, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States; John M. Leventhal, Yale Medical School, New Haven, CT, United States; Andrea G. Asnes, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States

Gunjan Tiyyagura, MD, MHS (she/her/hers)

Associate Professor of Pediatrics

Yale School of Medicine

New Haven, Connecticut, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Intimate partner violence (IPV) and child physical abuse frequently co-occur, yet children living with IPV are not routinely evaluated for abuse. We developed a model of Family-Centered Care (FCC) for IPV to evaluate children < 3-years-old reported to Child Protective Services (CPS) for IPV exposure. A community advisory board of stakeholders, including CPS leadership, IPV advocates and an IPV survivor, provided ongoing input.

Objective: To evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the FCC model.

Design/Methods: IPV-exposed children were evaluated in a child advocacy center for abusive injuries (with an examination and occult injury testing if indicated) by a child abuse pediatrician. At this visit, the abused caregiver was offered a real-time meeting with an IPV advocate who offered immediate access to services, such as emergency shelter or legal aid. We used a mixed-methods approach to evaluate the model. To assess acceptability, we interviewed 25 caregivers to assess experiences with FCC and analyzed transcribed data using the constant comparative method. For feasibility, we examined the percentage of 1) children < 3-years-old who were reported for IPV to one CPS office and evaluated with FCC, 2) caregivers who met an IPV advocate at the time of the child’s visit, and 3) caregivers who had follow-up visits with the advocate.

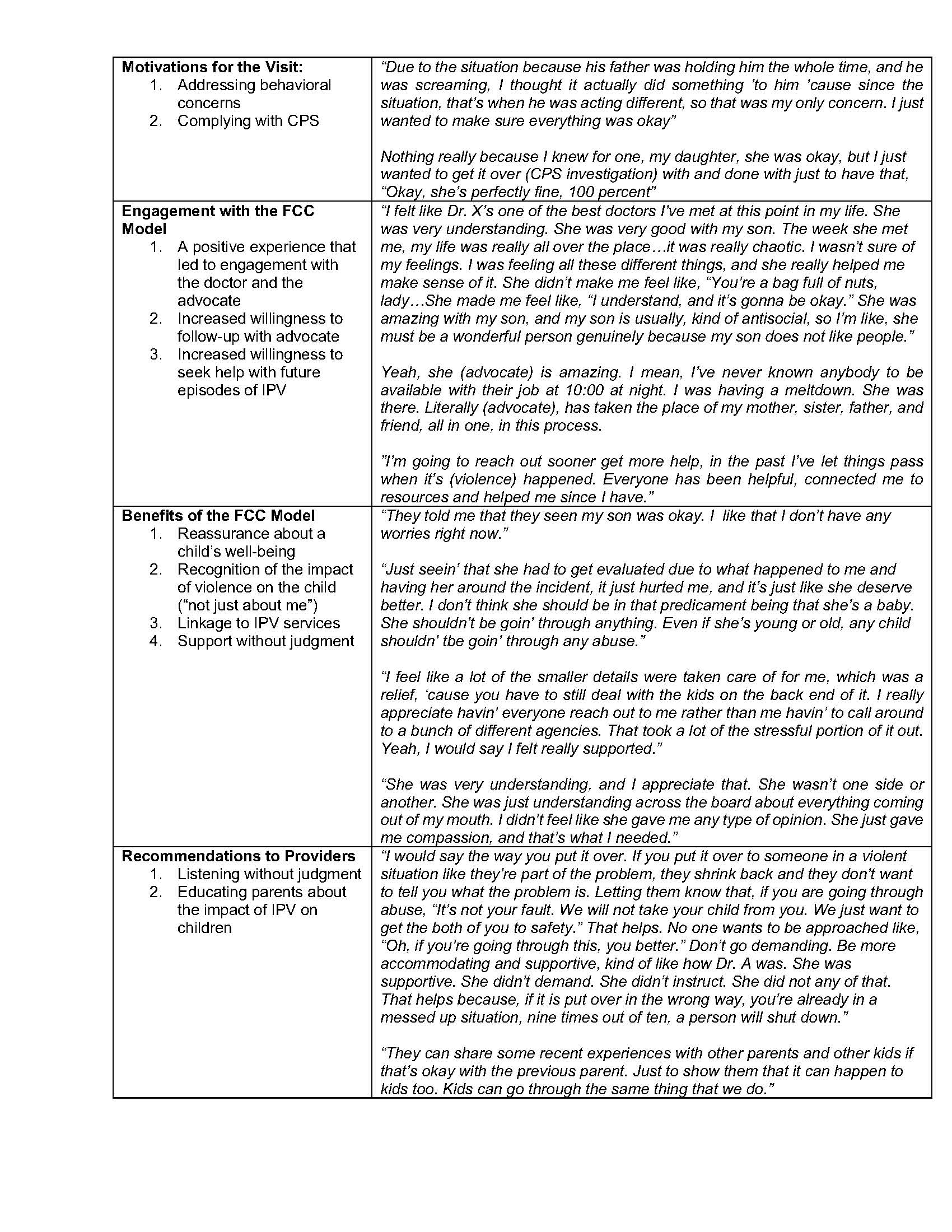

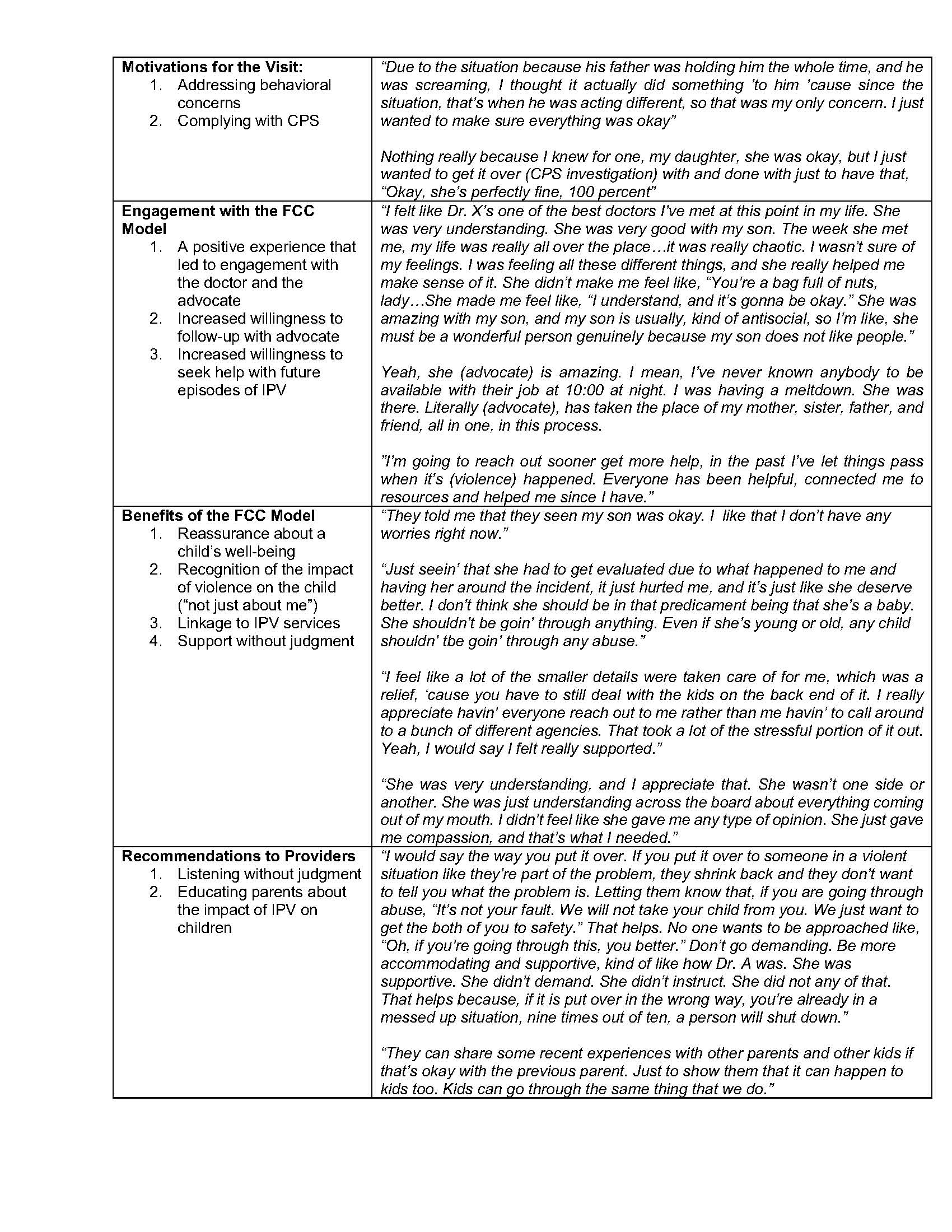

Results: Acceptability: Four categories emerged. Reflective quotations are in Table 1: 1. Motivations for the visit included addressing behavioral concerns in the child or complying with CPS. 2. Caregivers described engagement with the FCC model, both with the doctor and the advocate. Most described an increased willingness to seek help and to follow-up with the advocate after attending the FCC visit. 3. Benefits of the model included reassurance about a child’s wellbeing, recognition of the impact of IPV on the child (“not just about me”), linkage to IPV services, and support without judgment. 4. Recommendations to providers included listening without judgment and educating parents about how IPV impacts children. Feasibility: From 7/20 to 8/21, 36/107 (31%) children reported to CPS were evaluated with FCC. Of the 31 caregivers who accompanied the child, 5 were already linked to IPV services; 18/26 (69%) met with an IPV advocate during the child’s visit and 15/18 (83%) had >1 follow-up visit (range 1-40 contacts) with the advocate.Conclusion(s): A FCC model for IPV was both feasible and acceptable to IPV victims. FCC could improve the engagement of caregivers both with the evaluation of IPV-exposed children for abuse and potentially life-saving engagement with IPV services.

Reflective Quotations

Objective: To evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the FCC model.

Design/Methods: IPV-exposed children were evaluated in a child advocacy center for abusive injuries (with an examination and occult injury testing if indicated) by a child abuse pediatrician. At this visit, the abused caregiver was offered a real-time meeting with an IPV advocate who offered immediate access to services, such as emergency shelter or legal aid. We used a mixed-methods approach to evaluate the model. To assess acceptability, we interviewed 25 caregivers to assess experiences with FCC and analyzed transcribed data using the constant comparative method. For feasibility, we examined the percentage of 1) children < 3-years-old who were reported for IPV to one CPS office and evaluated with FCC, 2) caregivers who met an IPV advocate at the time of the child’s visit, and 3) caregivers who had follow-up visits with the advocate.

Results: Acceptability: Four categories emerged. Reflective quotations are in Table 1: 1. Motivations for the visit included addressing behavioral concerns in the child or complying with CPS. 2. Caregivers described engagement with the FCC model, both with the doctor and the advocate. Most described an increased willingness to seek help and to follow-up with the advocate after attending the FCC visit. 3. Benefits of the model included reassurance about a child’s wellbeing, recognition of the impact of IPV on the child (“not just about me”), linkage to IPV services, and support without judgment. 4. Recommendations to providers included listening without judgment and educating parents about how IPV impacts children. Feasibility: From 7/20 to 8/21, 36/107 (31%) children reported to CPS were evaluated with FCC. Of the 31 caregivers who accompanied the child, 5 were already linked to IPV services; 18/26 (69%) met with an IPV advocate during the child’s visit and 15/18 (83%) had >1 follow-up visit (range 1-40 contacts) with the advocate.Conclusion(s): A FCC model for IPV was both feasible and acceptable to IPV victims. FCC could improve the engagement of caregivers both with the evaluation of IPV-exposed children for abuse and potentially life-saving engagement with IPV services.

Reflective Quotations